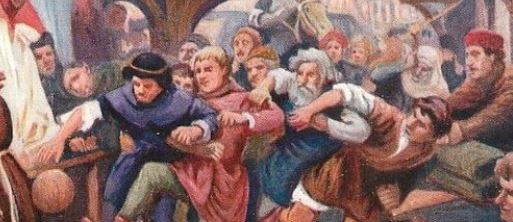

The term “medieval football” encompasses a wide variety of localized, informal football games that originated and were played in England during the Middle Ages. Also known as folk football, mob football, and Shrovetide football, these games are considered precursors to the modern codes of football. Compared to later forms of the sport, medieval matches were chaotic and had few rules.

The Middle Ages saw a rise in the popularity of these games, particularly played at Shrovetide (before Lent) across England, with notable activities in London. Although there is little concrete evidence to confirm their origins, it’s speculated that these games may have been influenced by Roman ball games, like harpastum, introduced during the Roman occupation. Historical accounts such as the ninth-century “Historia Brittonum” suggest that such ball games were already popular in southern Britain before the Norman Conquest, with one account indicating that a group of boys were engaged in ball play.

Mob football, the archaic form of the game, was typically played in towns and villages with virtually no player limit. Teams comprised of local residents would battle to move an inflated pig’s bladder from one end of the town to the other, using any means necessary short of manslaughter or murder. In some cases, the goal was to kick the bladder onto the balcony of the opposing team’s church, adding a unique local twist to the game.

Despite urban legends suggesting a violent origin—like the ritual of “kicking the Dane’s head”—such tales are widely considered apocryphal. The decline of these rough and tumble games began in the 19th century following the Highway Act of 1835, which banned playing football on public highways. Nevertheless, the tradition persisted in some areas and continues to this day in several towns. Noteworthy are the Ba game played during Christmas and New Year in Kirkwall, Orkney Islands, Scotland; Uppies and Downies over Easter in Workington, Cumbria; and the Royal Shrovetide Football Match on Shrove Tuesday and Ash Wednesday in Ashbourne, Derbyshire.

Surviving images of medieval football are rare but telling. A notable fourteenth-century wooden misericord carving from Gloucester Cathedral shows two young men energetically converging with a ball mid-air between them. Another historical image housed in the British Museum features a group of men around a large, seamed ball, suggesting the rough nature of the game.

These early forms of football, which often involved merely “ball play” or “playing at ball,” highlight a robust tradition that has shaped the evolution of football into the structured, rule-bound sport we recognize today. The enduring appeal of these medieval games in certain regions underscores their cultural significance and the deep roots of communal sports in England’s social fabric.